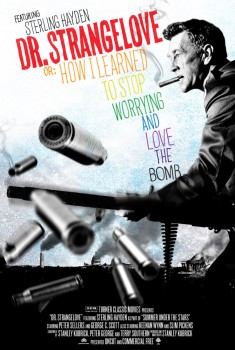

The iconic 1960s Cold War movie Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is a film about the logic of mutually assured destruction as a stability generating mechanism in the rivalry between the two nuclear armed foes of America and the Soviet Union. Aside from commentary on the idea of credible commitments and making sure your rival knows about the commitments you’ve made, the film is certainly many other things too: an excellent black comedy, a great collaboration between Peter Sellers and Stanley Kubrick, an investigation of America and the international system, etc. etc. The film also includes some great lines while its cultural impact has shown up in The Simpsons (i.e., the memorable bomb riding scene).

The iconic 1960s Cold War movie Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb is a film about the logic of mutually assured destruction as a stability generating mechanism in the rivalry between the two nuclear armed foes of America and the Soviet Union. Aside from commentary on the idea of credible commitments and making sure your rival knows about the commitments you’ve made, the film is certainly many other things too: an excellent black comedy, a great collaboration between Peter Sellers and Stanley Kubrick, an investigation of America and the international system, etc. etc. The film also includes some great lines while its cultural impact has shown up in The Simpsons (i.e., the memorable bomb riding scene).

Underpinning nearly all global interactions at the time Dr Strangelove was made were calculations of the Cold War rivalry between Russia and the US. Each of their respective allies and clients might have had local problems or conflicts, but underneath these local issues, Cold War logic played out. Take for example the early 1960s war in the Congo: the US and Soviet Union sought influence at the expense of their Cold War foe and engaged in proxy-engagements. Local political groups to the Congo, well-armed militia, and so forth, played lip service to the logic of the Cold War divide to gain resources and power. Hardly any of them had true anti-Communist or pro-Western ideologies, rather they knew resources could be had by claiming to lead a revolution for the people or that they alone were the bulwark against expansionist, anti-freedom red hordes. Certainly you don’t need to know much about the Cold War balance of power to appreciate and understand the ‘Congo Crisis’ as it was known, but this additional information helps to explain some of the key undercurrents of the conflict (e.g., why the US turned down a request from the UN for tactical air support, but allowed them to supply strategic airlift, or why Canadians played a key part in the UN’s operations). In another example, the Angolan Civil War involved many players with ostensibly local issues. There was involvement of a number of countries and interests, yet in the background involvement from the Cold War rivals funded and armed players in the conflict as they continued their strategic game, often hidden game.

What does this have to do with the MBA program you might ask? I see Managerial Economics taught by Dr Moore in a similar light. Let me explain.

The lectures we’re having revolve around broad economic processes and decision making. Take for example the determinants of a long-term supply and demand for an entire market. A slight shift in commodity prices may have ripple effects that change the number of firms working in a tangentially related market. The result is that supply prices for that industry may change and then the number of firms which are now viable increases or decreases. One firm may drop out of the market because its marketing isn’t as good, or lose market share due to personnel reasons. There are entirely tactical explanations. On a more strategic level though, we can observe that the market as a whole changed, and the weakest or least able firm ceases to operate. In effect there is an undercurrent at work which informs everyday decisions for firms which isn’t immediately apparent on casual observation.

This hit home when my MBA classmate Ben Sigston pointed out a front page item in the Globe and Mail the other day on a break from Dr Moore’s class: Apple’s big iPad strategy shift. The first paragraph immediately speaks to economic decision making we were covering in class: Apple is “selling hardware at a premium, and giving software away free” plus it’s revamped its tablet pricing strategy so that “it can still own the high end of the market, while letting the industry’s most intense battle play out at the lower end.” Giving away software is a strategic move to capture or retain demand for their products. Likewise, a recent announcement by Shell to go ahead with an oilsands project has a host of immediate concerns related to environment, community, or commercial impact for Alberta and Canada. Yet the underlying logic at work with the decision to move on the project is economic in nature: this is a decision that plays a part in maximizing shareholder value for Shell—or at least that’s the hope.

This hit home when my MBA classmate Ben Sigston pointed out a front page item in the Globe and Mail the other day on a break from Dr Moore’s class: Apple’s big iPad strategy shift. The first paragraph immediately speaks to economic decision making we were covering in class: Apple is “selling hardware at a premium, and giving software away free” plus it’s revamped its tablet pricing strategy so that “it can still own the high end of the market, while letting the industry’s most intense battle play out at the lower end.” Giving away software is a strategic move to capture or retain demand for their products. Likewise, a recent announcement by Shell to go ahead with an oilsands project has a host of immediate concerns related to environment, community, or commercial impact for Alberta and Canada. Yet the underlying logic at work with the decision to move on the project is economic in nature: this is a decision that plays a part in maximizing shareholder value for Shell—or at least that’s the hope.

Understanding that there is a broader strategic game at play helps to illuminate why certain changes happen, albeit it doesn’t describe everything—nor does it claim too. The tools and models we’re training in during this course help us gain a broader understanding of the underlying forces at work which impact on business decisions. Trusting in what the models reveal—and what they don’t—as well as understanding the broader effects at work in the economic system, in the same way that the knowing the nuclear balance of power and nuclear weapons broadly effected the logic of the international system during the Cold War, is the goal of the class to help provide context to business decisions overall.

Ryan Cross is a current MBA student at Beedie. He spent a number of years prior to starting his MBA conducting research, publishing, and presenting papers on military intelligence tools, on UN peacekeeping operations, and the ethics of war. Ryan tweets at @ryanwcross and can be contacted at rca34@sfu.ca.